Building health policy research and implementation science capabilities at GERI

26 August 2025

GERI welcomed our visiting experts, Professor John Lavis of the McMaster Health Forum and Professor Sharon Straus of Unity Health Toronto, for a week of discussions and workshops the Institute.

As part of GERI’s 10th anniversary celebrations, GERI welcomed our international experts Professor John N. Lavis and Professor Sharon Straus for a week of scientific exchanges, discussions and workshops both at the Institute and beyond from 7 to 11 July 2025.

Professor Lavis is GERI’s International Scientific Advisor. He directs Canada’s McMaster Health Forum and the WHO Collaborating Centre for Evidence-Informed Policy, and co-leads the Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges.

Professor Straus is an Adjunct Scientist at GERI. She is Director of the Knowledge Translation Program, Executive Vice-President, Clinical Programs and Chief Medical Officer at Unity Health Toronto, and a Professor in the Department of Medicine, University of Toronto.

Supporting evidence-informed policymaking

“In Singapore, there’s a lot of attention on research and innovation systems, where performance is often measured by grants, publications, patents and licensing revenue,” Professor Lavis noted. “What’s also important is building a robust evidence-support system, where the evidence needs of health system decision-makers, advisors and implementers are also met.”

Professor Lavis has been providing capacity-building to GERI’s Health Policy Group researchers involved in projects to inform national policies around the screening and management of frailty and dementia. Some key takeaways that emerged over the course of Professor Lavis’s talks at GERI include:

Be attuned to the health policy and stakeholder landscape. The dynamism of the policy field requires a nimble approach in order for the right research evidence to reach decision-makers at the right time. “In policy, you often have people entering and leaving roles, which affects the potential for transformation. Be attentive to windows of opportunity (in the policymaking process) and respond quickly,” said Professor Lavis.

Develop “general contracting” skills to match the right forms of evidence to a given policy need. In Professor Lavis’s analogy, general contractors are relied on by homeowners to assess and identify the right renovation fixes and the right type of “trades” to make the fixes. Similarly, researchers could be intermediaries that policymakers can depend on, to clarify and scope research questions appropriately, and deploy the right “tools” – from system and policy analysis skills, as well as capabilities in evidence synthesis, rapid research methods and stakeholder engagement – to meet the needs of policymakers.

Offer contextualised research evidence to policymakers. Instead of offering a single form of evidence (such as qualitative research), researchers should seek to contextualise local study findings alongside other forms of evidence, such as existing evidence syntheses, or consider complementing evidence briefs with stakeholder dialogues. Researchers should also think about existing system arrangements (such as financing systems and care delivery design), and the sphere of influence of their targeted policymakers, and contextualise their messages in relation to these factors.

Leveraging implementation science for meaningful research impact

Researchers looking to enhance the adoption of their research evidence into routine care and practice often encounter practical hurdles. Professor Straus has been working with researchers at GERI to enhance their application of implementation science principles to various translational research projects, in areas ranging from Advance Care Planning implementation to evaluating Community Care Apartments for older adults.

Some key ideas that arose from Professor Straus’ interactive workshops and discussions at GERI include:

Make implementation science more user-friendly and accessible. If findings are jargon-filled, impractical or not brought to the point of care, chances of its uptake and subsequent potential for lasting impact are diminished. “You don’t have to be a scientist to do implementation science,” Professor Straus said. “Researchers should think about both implementation and dissemination, and the science and practice of both. (…) The irony is that sometimes, we get so caught up in advancing knowledge in this field, that we don’t stop to think about ensuring that it actually gets used.”

Engage stakeholders meaningfully throughout the project cycle, moving beyond tokenistic engagement to advance co-creation methods. For example, discuss shortlisted implementation strategies with stakeholders to glean insights into their potential feasibility and implementability over time. The team’s methods of engaging stakeholders should be discussed at the outset, taking into account stakeholders’ preferences such as which project phase they would like to contribute to and their desired level of involvement. Ideally, researchers should also plan to evaluate the engagement process itself afterwards.

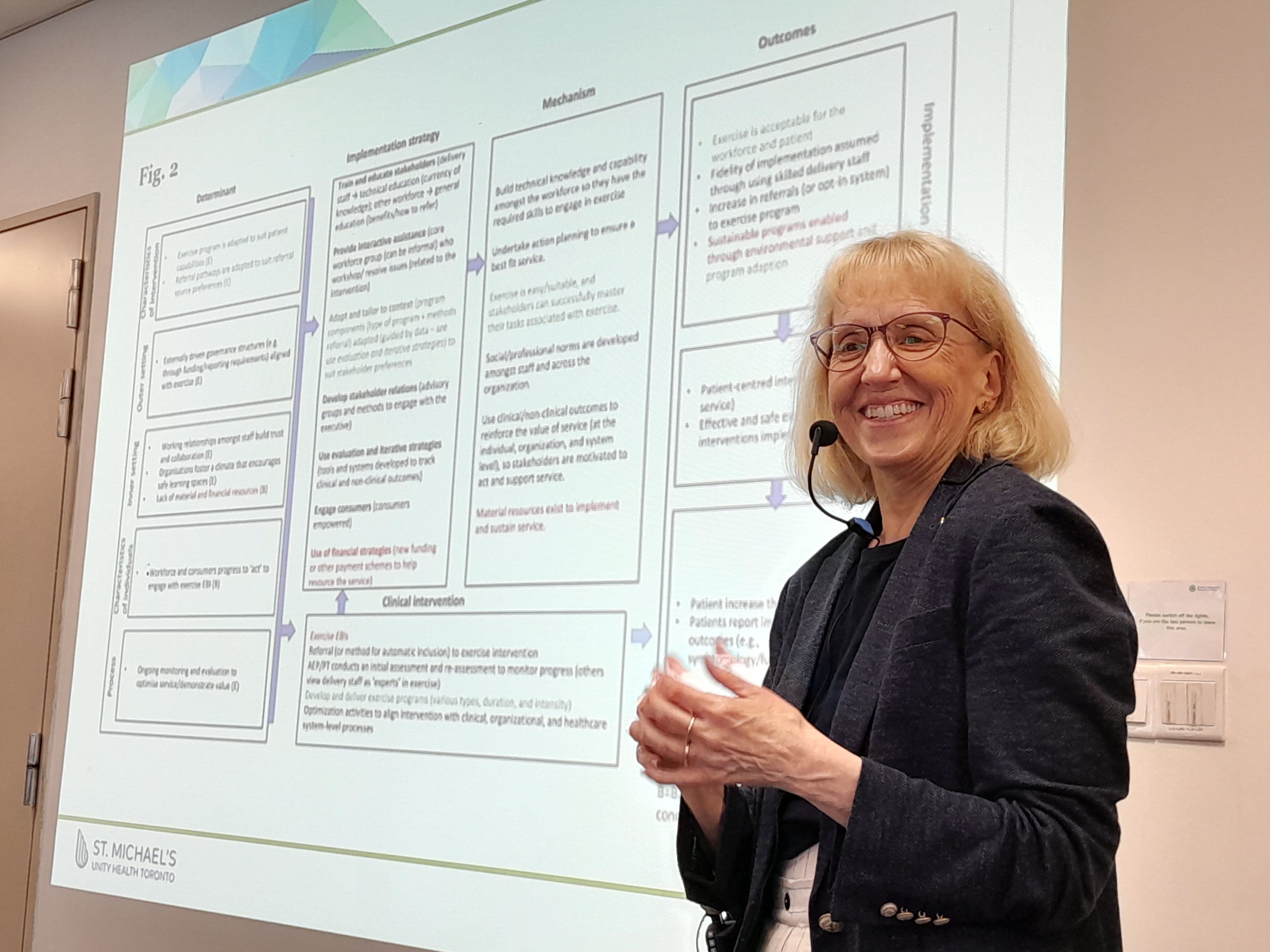

Systematise implementation planning and monitoring. Professor Straus highlighted how logic models can serve as roadmaps for implementation planning. By developing logic models, researchers are spurred to think about how to incorporate research sustainability from the start, as well as how to operationalise programme rollout, such as specifying implementation strategies and identifying determinants. For scale-up, it is important to identify barriers to scalability even at the start of the project, and to continuously monitor impact over time.

.png)

As part of their visit to GERI, Professor Lavis and Professor Straus also met with partners in Singapore’s healthcare research and geriatrics space. Click here to read more.

Read highlights of their plenary presentations at GERI’s 10th Anniversary Research Symposium here.